How familiar are you with Black Canadian history?

“So many people educated in Canada, or external to Canada, don't know about the long-standing presence of Black people in this country,” says Funké Aladejebi, an assistant professor with the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of History. “This breadth of knowledge on Black Canadian history often gets ignored or is not often inserted into broader courses on Canadian history.”

Determined to change this, Aladejebi is teaching a year-long course entitled Black Canadian History. It’s part of a new Certificate in Black Canadian Studies offered through University College and open to all Arts & Science students.

“Many of the students in this class come from health and science, equity studies and Indigenous studies, and a lot of them like the idea of being able to say they have specific expertise on Black Canadian studies more broadly,” says Aladejebi.

The course exposes students to the Black experience from the 17th century to the present.

“It's trying to give students a broad overview of the movements and migrations of persons of African descent into the land that is now called Canada, and thinking in complex ways about how people were living and existing in this country,” says Aladejebi.

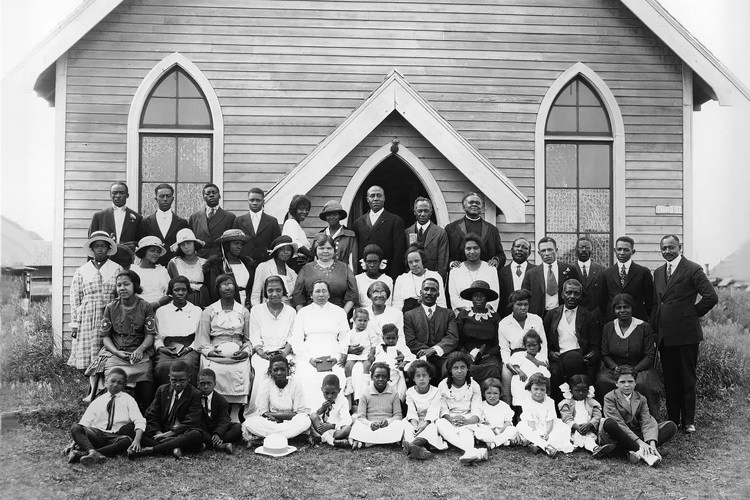

The course goes as far back as 1604, the year of the earliest records of persons of African descent in Canada. Moving across time, the course covers chapters such as the experience of the Black Loyalists — people of African descent who sided with the British cause during the American Revolutionary War — passengers of the Underground Railroad, as well as lesser-known movements to the West Coast, Prairies and Maritimes.

“We tend to forget about these regions where Black people resided in smaller numbers,” says Aladejebi. “But it's our responsibility as historians to show the breadth of where Black people have been, and where they still are.”

So many people educated in Canada, or external to Canada, don't know about the long-standing presence of Black people in this country. This breadth of knowledge on Black Canadian history often gets ignored or is not often inserted into broader courses on Canadian history.

For example, most Canadians are unfamiliar with the history of the Jamaican Maroons in Nova Scotia.

In 1796, three ships brought more than 500 Maroons — men, women and children — to Halifax from Jamaica, where they had fought for independence from Britain. To curtail British anxieties over resistance and rebellion among enslaved populations in Jamaica, the Maroons were forcibly exiled to Nova Scotia.

Despite an inhospitable reception they flourished, maintaining a strong sense of community in exile. They were connected to the city’s larger community, having been involved in the construction of the Halifax Citadel. However, they found the harsh Nova Scotia winters less than desirable and chose to leave Nova Scotia and immigrate to the free Black colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa in 1800.

“But it’s widely believed some Maroons stayed behind and their continued presence is reflected in the surnames, accents, idioms, customs, oral histories and traditions of African Nova Scotians,” says Aladejebi.

As she covers the material, Aladejebi is intrigued by the range of emotions the students experience. At times, class discussions are challenging and difficult.

“They move through emotional stages where they are surprised at first and then get frustrated because of what they didn't know,” says Aladejebi. “The Black students go through a variety of feelings, but at end of the class, they’re feeling like they know a little bit more about themselves and the experience of persons of African descent.

We all come with our limitations, biases and prejudices. This course is helping us to think about where they come from, why they exist, and how we can interpret them. It's about interrupting the cycles, unlearning what we thought we knew, and re-imagining something better.

“Non-Black students also go through a series of emotions. They feel better equipped to talk about Black Canadian history, they’re able to better understand various social relationships that are part of Black experiences across the diaspora.”

The second half of the course dives into more contemporary issues such as racial violence, anti-Black racism, current immigration trends, equity and inclusion for Black communities, and Black injustice in Canada.

Funké Aladejebi is an assistant professor with the Department of History.

“We never just stay in the history, we always bring it to the contemporary with these historical foundations and track why this continues to exist today,” says Aladejebi. “By the time we move through the course, students understand the roots of anti-Black racism in Canada, and they're able to navigate institutions in a clearer way.”

As the second half of the course is a little more personal, anxious moments are not uncommon.

“Students have to talk about, ‘What was my experience in school? What was my experience and engagement with policing and the judicial system?’ So we go through pockets where students are nervous about saying the right and wrong things.”

But from the anxiousness and tension come knowledge and understanding for students like Dacian Dawes, a third-year member of St. Michael’s College double majoring in political science and critical studies in equity and solidarity, with a minor in African studies and a certificate in Black Canadian history.

“As a Black Canadian political science major pursuing a career as a policy analyst, the course’s material, conversations and activities are crucial to both my academic and professional development,” says Dawes. “It has increased my understanding of systemic inequalities, inspiring me to use this information to build on my political science studies and future career.”

Erinayo Adediwura Oyeladun, a second-year student in African studies and a member of Trinity College has been empowered by studying the work of Black Canadian history scholars, and sees how historical understanding can be a powerful tool in creating change.

The historians’ research teaches me the importance of situating your work as more than just an intellectual discovery. Your work should also represent your community and serve a broader purpose in making a positive impact for your community.

“The historians’ research teaches me the importance of situating your work as more than just an intellectual discovery. Your work should also represent your community and serve a broader purpose in making a positive impact for your community.”

For Aladejebi, teaching the course has been just as energizing, with her students continually challenging her in the way she teaches and delivers — and receives — information.

“We all come with our limitations, biases and prejudices. This course is helping us to think about where they come from, why they exist, and how we can interpret them. It's about interrupting the cycles, unlearning what we thought we knew, and re-imagining something better.”