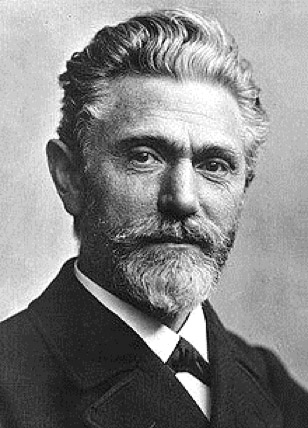

(August Bebel)

(August Bebel)

Before the First World War, August Bebel (1840-1913) was the charismatic leader of the largest socialist party in Germany, Europe, and the world. Whereas barely a dozen people attended Karl Marx’s burial in London’s Highgate Cemetery in 1883, thirty years later Bebel’s funeral attracted 60,000 mourners and lasted for two days. It was the most impressive working-class gathering in Imperial Germany. How did workers come to revere a man who began adult life in the 1860s as an itinerant master turner producing doorknobs from buffalo horns but by 1900 exercised unassailable authority within Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD)? Bebel’s party grew to over one million members by the First World War and dominated the Second International. The Free Trade Unions affiliated with the SPD had over two million members. In Germany’s national elections of 1912, every third voter cast a ballot for the “party of revolution”—an ominous sign for a state preparing for war.

This research project asks how German workers “found” Bebel, embraced him as “their emperor,” and came to put their faith in Social Democracy’s message. If many of them needed to be convinced, most non-working-class Germans believed instinctively that Bebel and his followers sought “the total overthrow of the existing state and society.” Bebel and the SPD retained their pariah status in the view of German elites and the state from the 1870s to 1913. Loyalty to the nation became a litmus test of German citizenship: in the words of Emperor Wilhelm II, Social Democrats were “scoundrels without a country.” Bebel’s life thus illuminates a schism that ran through the heart of German political culture, separating socialists from everyone else.

This project also asks how much celebrity really mattered in the age of mass politics, mass culture, and the mass press. Bebel was a master at exploiting monarchical, colonial, and other scandals, using them to identify myriad injustices in his world. The fortunes of Bebel and his party throw into stark relief the difficulty of implementing liberté, égalité, and fraternité some 125 years after the French Revolution—that is, before either the Russian Revolution or Nazism offered more radical options for realizing a utopian state. Germany’s newly ascendant bourgeoisie wanted no part of a global order based on the rights of workers, women, and other oppressed groups. In a way, Bebel became the bourgeoisie’s anti-Kaiser too, a “German Robespierre” poised to unleash a Reign of Terror (as in France during the 1790s). Yet Bebel saw in socialism the possibility of justice for all, and he saw in patient reform a non-violent path toward democracy on a supra-national scale. This project – supported by Guggenheim and Killam fellowships and SSHRC grants – will explore these distinctions to discover how the title of “emperor” conferred iconic authority on Bebel and what these developments meant for the future of democracy.

Article: “August Bebel: A Life for Social Justice and Democratic Reform”

Principal Investigator: James Retallack